Historic Celebrations of the Emancipation Proclamation in Shasta County

[this article originally published in Zombie Ant issue 0.5]

Juneteenth may be a somewhat new holiday to some of us, but it actually dates back to 1866. The holiday commemorates the reading of federal orders in Galveston, Texas on June 19, 1865 proclaiming all enslaved people in Texas were now free. Although enslaved people in Confederate states were freed by the Emancipation Proclamation on January 1, 1863, the lack of Union troops in the state allowed the practice of slavery to continue unabated until 1865.

California, of course, was admitted to the Union in 1850 as a “free” state, though de facto slavery of indigenous peoples continued for many years afterward, de juris segregation for many decades, and de facto segregation still continues today.

The Shasta Courier doesn’t record if or how local African-Americans celebrated the Emancipation, but accounts of local celebrations began to appear in local papers no later than 1867.

The fourth anniversary of the Emancipation Proclamation was celebrated on January 1, 1867 by “the colored people of this town” at the stately Empire Hotel on Main Street in Shasta, which stood just west of where the courthouse museum is located today. The celebration included a banquet, a ball, and an oration by George Bailey, an African-American man who emigrated to Shasta from New Bedford, Massachusetts several years earlier. The Courier reported the hall was “adorned with flags, shields, mottoes, eagles, pictures of Washington, Lincoln, Grant, Sherman, etc., and the entire affair, from beginning to end, was quite credible.” The paper even printed Mr. Bailey’s oration in full, as I will below:

“Mr. President, Ladies and Gentlemen: I thank you for the honor conferred upon me, and at the same time I feel my inability to properly perform, the task assigned me; but you will please remember that mistakes are incident to, and inseparable from, ignorance, and in no wise emenating from the heart.

This is the third anniversary of the Emancipation Proclamation, and to us it is fraught with an interest such as no other day possesses, save one, in the calendar of time second only to the day on which the Great Creator of the universe rested from his labors.

When a race of people have been hound down by unjust laws, and denied rights and privileges accorded to all other members of the community around them, it has been the custom in all time to celebrate their emancipation by some particular observance of the day thus signalized. Thus we find that among nearly all nations some particular day is regarded as possessing a sacredness second only to that devoted to Divine worship. We, as a people, have hitherto been almost the only exception to this rule; but the rosy morn that ushered in the First Day of January, 1863, gave to us a day of thanksgiving and praise ‘a day of universal joy’ a day on which, laying aside all petty controversies and personal differences, and meeting upon one common ground, united by a common sympathy, we may forget all else save that we are one common brotherhood, and that as we have suffered together, so also will we rejoice together.

For long years has the cry of oppression ascended from our brothers in the South, and not there alone was sadness ; but from hearths in the freedom loving North, around which were gathered the sable sons and daughters of Adam, has ascended the cry: ‘How long, O! Lord, how long?’ and there, too, has joy descended like an angel with healing on its wings.

Rejoice, aye. rejoice, men of our sable race, that the aspirations of genius, smothered in your breasts by tyranny, shall he transmitted by you to your sons, and in them be brought to their full fruition. Rejoice, women of our dusky race, that you shall no more be compelled to witness the evidence of compulsory submission depicted upon the faces of your children, and that you are no longer compelled to yield obedience to the requirements of brutal oppressors. Rejoice, one and all, that henceforth the paths that lead to the temple in which the arts and sciences are enshrined are unobstructed by false prejudices ; for free in body, and unfettered in intellect, we will march on until the names of Africa’s sons shall be inscribed upon the golden tablets which shine in the loftiest niche of the Temple of Fame.

I now propose to glance at the position we occupied a few years ago, and notice some of the changes that have taken place. Recollect that I will ‘nothing extenuate nor aught set down in malice.’ It has been but a few years since the Fugitive Slave Act was discussed, submitted, and became a law. When that act became a law there was virtually no longer a free man, woman or child of color within the confines of these United States. After this came the Dred Scott decision a decision as chilling to us as the night winds blown from the clouds that encircle the Poles declaring to us in words of frozen tyranny that the black man had no rights which the white man was bound to respect; or, in other words, declaring that one-sixth of the people of the United States had no right even to life unless it happened to suit the capricious whims of those among whom their lot was cast. We all remember, too, the exodus of the colored people from California in 1852-3, consequent upon the Act of the Legislature requiring all persons of color to leave the State unless they could procure white vouchers for their honesty and morality ; and for vetoing that bill John B. Weller gained immortal renown among the colored people of this State. But I will pass over the rest of our wrongs in silence, nor reopen wounds that are nearly healed. I will turn to the other side of the picture.

To-day we are recognized as an integral portion of the population that goes to make up the People of the United States, and have the right to testify in the Courts of law, the right to accumulate property, and the full protection of the law in the enjoyment of the same, from Maine to San Francisco, and the right also to travel all over this broad country without challenge. In gaining all this we have done well ; but we still have troubles, and to overcome them let us observe the same patience as heretofore, and before long we will be able to hail the watchman upon the tower of liberty with ‘Watchman, what of the night?’ and receive the cheering answer: ‘The night passeth away, the daystar has arisen, and the rosy gleams in the cast herald the approach of a perfect freedom.’

Our father, Abraham Lincoln, the great, the good! His generous, loving heart is now still in death, hut let us try to emulate his many virtues, and teach our children to love, honor and revere his memory. And now let us take the starry Flag, so often borne on fields of blood as our symbol ; its red, as emblematic of the patriotic blood that we are willing to shed in its defense; the white, of our unsullied loyalty ; and the blue, of our unswerving fidelity to freedom ; and the whole flag as symbolic of our devotion to the Union, in defense of which death shall have no terrors for us.”

The oration of George Bailey, as printed in the Shasta Courier of January 5, 1867.

Another celebration, consisting of a ball and supper, followed the next year, where the Courier noted (in a much shorter article) that Mr. Bailey “acquitted himself creditably” in the oration.

The Courier didn’t report on any additional celebrations, if they occurred, through at least 1872. The next celebration I have located (so far) occured in Redding, on New Year’s Day 1903.

Redding actually had quite a large African American population in the late 1800s and early 1900s. According to the 1900 Census, African Americans made up 4.1% of Redding’s population, a much larger percentage than the 1900 statewide percentage of 0.75% and nearly 3.5 times their percentage of Redding’s population in the 2010 Census.

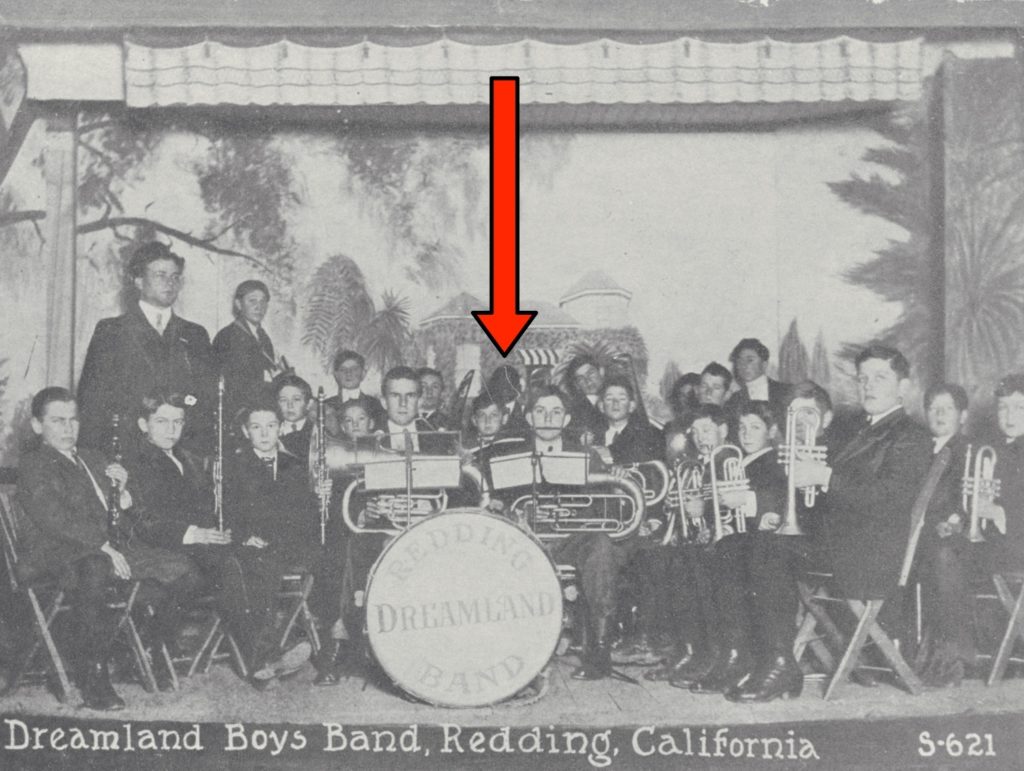

The local African American community had their own Masonic lodge, chapter of Eastern Star, baseball team, coronet band, political club, and a church that still stands on the corner of Trinity and California Street downtown—the oldest church in Redding.

The year 1903 would have been the 40th anniversary of the Emancipation Proclamation and the local community was determined to have a grand celebration to commemorate it.

The event was hosted by local African American Masonic lodge (African Americans were not welcome in “mainline” lodges until about the 1970s) and drew attendees from as far as Sacramento. The lodge rented out the second-floor hall of the Jacobson building downtown and decorated it with red, white, and blue streamers. The evening opened with an invocation by Reverend E.H. Brown, who also served as master of ceremonies. The “national hymn” was sung next, though it’s not clear what exactly was meant by this—the “Star-Spangled Banner” did not formally become our national anthem until 1931. Next came the reading of the Emancipation Proclamation, followed by a program of musical performances, addresses, speeches, and dancing. The Courier-Free Press gushed “one does not exaggerate in saying that it was the greatest event in the history of Redding’s colored society.”

There remains much research yet to do, but celebrations were also held in at least 1906, 1907, 1908, and again for the 50th anniversary in 1913.

Unfortunately, the 50th anniversary was not without incident. A group of young white men—Fred Eckles, George Lack, Roy Winsell, and Ray Winsell—crashed the event and caused trouble. The account in the January 7, 1907 Searchlght is (no doubt deliberately) vague, but it appears there was disagreement about with whom the the crashers would be dancing. Harsh language was used and the four were forcibly ejected from the premises. “The celebration practically broke up and several fist fights were the result during the early morning hours,” the Searchlight wrote.

The local African-American community was so incensed at this assault that that two young men, Henry Coleman Jr. and Beauford Clark, swore out warrants against Eckles, Lack, and the Winsells, who were arrested and brought before Judge Herzinger.

George Lack was released after, according to the Searchlight, “there seemed to be a misapprehension on the part of the complainants that he was in part responsible for the trouble.” The other three plead “not-guilty” to charges of disturbing the peace and were released on bail of $50 each (nearly $1,300 in 2020 dollars).

A few days later, Eckles and Ray Winsell changed their pleas to guilty and were fined $15 each, (just shy of $400 in 2020 dollars). The charge against Roy Winsell was dismissed.

Seven years later, according to the 1920 Census, African Americans made up just 0.9% of Redding’s population. It’s yet not clear why there was an exodus of Redding’s one-time sizable African-American population. Research has not yet turned up any recorded major traumatic events that could explain it, but it is worth noting that is widely agreed that the Great Depression hit Redding ten years earlier than the rest of the country with the collapse of the local copper industry in 1919. It is hopefully just a case of families choosing to seek better opportunities elsewhere.